UL recently tested and promulgated a listing for a new two-hour load bearing wood-frame wall assembly containing pressure impregnated fire-retardant-treated wood (FRTW), a move that makes it quicker and easier for building officials to approve plans for Type III construction.

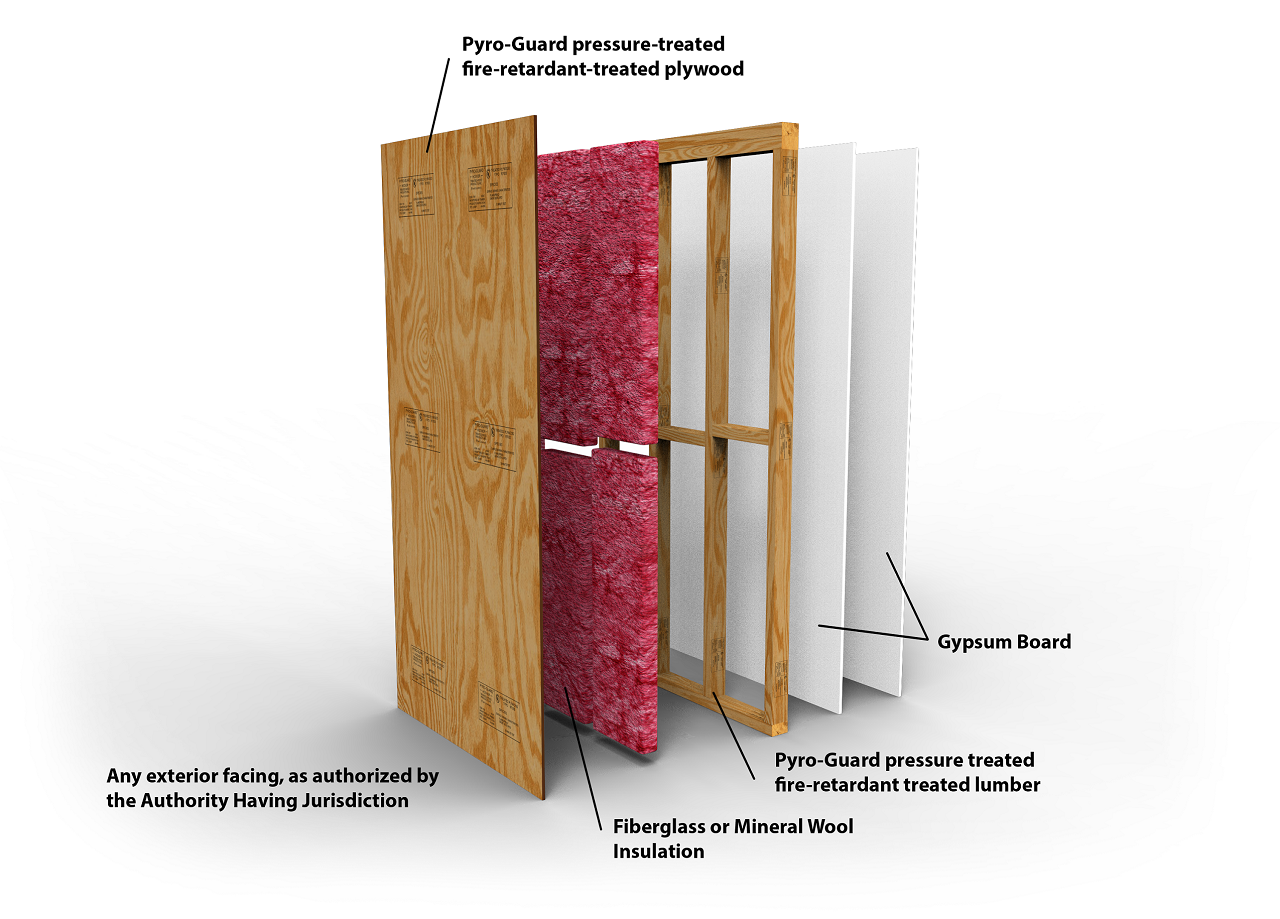

The new fire resistive listing, UL Design No. V314, is the first fire-resistance rated bearing wall assembly to be tested by UL with FRTW. The design calls for the use of Pyro-Guard® FRT lumber and plywood. A product of Hoover Treated Wood Products, Pyro-Guard lumber and plywood is widely used for weather protected applications in buildings of Type I, II, and III construction.

UL recently tested and promulgated a listing for a new two-hour load bearing wood-frame wall assembly containing pressure impregnated fire-retardant-treated wood (FRTW), a move that makes it quicker and easier for building officials to approve plans for Type III construction.

The new fire resistive listing, UL Design No. V314, is the first fire-resistance rated bearing wall assembly to be tested by UL with FRTW. The design calls for the use of Pyro-Guard® FRT lumber and plywood. A product of Hoover Treated Wood Products, Pyro-Guard lumber and plywood is widely used for weather protected applications in buildings of Type I, II, and III construction.

UL has allowed FRTW to be substitute for untreated wood in their fire-resistance listings for wood-frame wall assemblies for many years. However, UL had not tested FRTW in any of these assemblies. Therefore, there were no specific listings for FRTW wood-frame assemblies at UL. In order to use these wood-frame assemblies in noncombustible types of construction, designers must modify the assemblies by specifying substitution of FRTW studs and FRTW plywood for the untreated wood studs and sheathing in the UL listing.

Saving Steps

UL Design No. V314, approved in 2015, makes those modifications unnecessary. Dave Bueche, marketing manager for Hoover, says the listing saves specifiers time during the design process and building officials a step during the approval process.

“That’s part of why this is unique,” Bueche says. “There’s an assembly that has fire-retardant-treated wood in it, and now [designers] don’t have to go through the process. And generally, when a building official or fire official sees a UL design, they accept it readily.”

Matthew Schumann, UL’s industry manager for fire resistance and fire containment, agrees that the listing speeds up approvals.

“If you have a UL design with everything specified,” he says, “Hoover can say, ‘Here is the test system,’ and the designer can say, ‘Here is what we want to use.’ It gets quicker approval.”

An architect who specifies a tested design but modifies it by substituting other fire retardant-treated wood for an original material, on the other hand, could “raise a red flag” that “could make somebody tear the wall out,” Schumann notes.

Preventing Fires

UL’s listing of the proprietary design with FRTW mean architects will continue to specify wood for more—and somewhat taller—residential buildings. Because Section 602.3 of the IBC allows FRTW in exterior wall assemblies in lieu of noncombustible materials—when the required fire-resistance rating of the wall is two hours or fewer—many buildings constructed entirely of wood can be just as large and as high as noncombustible buildings.

Untreated wood naturally has a limited, built-in fire resistance because of its moisture content. In the early stages of a fire, wood actually strengthens as the heat depletes that moisture. Also, because wood is an effective insulator, heat on its surface—even if it chars the surface—transfers to its core slowly, giving a building’s occupants some time to evacuate and firefighters some time to quench the fire.

Once a fire-retardant treatment like Pyro-Guard is added, however, wood maintains its structural integrity and burns at an even slower rate and will not spread the fire from one part of a building to another. And once the heat source is removed, pressure impregnated fire-retardant-treated wood will extinguish itself.

IBC Section 2303.2 requires FRTW to have a flame spread index of 25 or less—a measure of a building material’s surface burning characteristics in a 10 minute test—and to show no significant progressive combustion during an extended ASTME E84 or UL 723 test that lasts an additional 20 minutes for a total test duration of 30 minutes.

Common Choice

UL updated V314 in late 2016 to include fiberglass insulation in the assembly. The original design was limited to mineral wool insulation, which is still allowed.

According to Bueche, contractor’s use of fiberglass insulation in the V314 assembly has become “pretty commonplace” in the few months since its addition to the listing.

“There’s an immediate savings for the systems that have already been designed” if the specifiers switch from mineral wool to fiberglass insulation before building, Bueche says. “From the point of view of contractors, this is a much less-expensive system than others out there [that use costlier noncombustible materials], so they are quite enthusiastic about it. The design professionals see it as a simple solution for their needs, so they’re very enthusiastic about it as well.”

Schumann says that reaction is not unexpected, saying most new UL designs often result from innovations by manufacturers hoping to fill a hole in the market. “They know that people may be doing certain things in the field during their construction process, and they develop a process or design to solve that problem.”

Schumann expects to see other UL testing of assemblies using FRTW for other parts of a building—besides exterior walls. “There’s potential in three to five years that we will see 10 more designs with the same premise as this, but used elsewhere in the building.”