The 2018 International Building Code clarifies that fire-retardant-treated wood (FRTW) manufactured without using the pressure process must be impregnated with chemicals.

New language in the 2018 IBC clarifies for building officials the regulations for using FRTW in Types I, II and III construction, which call for the use of non-combustible materials or FRTW.

The 2018 International Building Code clarifies that fire-retardant-treated wood (FRTW) manufactured without using the pressure process must be impregnated with chemicals.

New language in the 2018 IBC clarifies for building officials the regulations for using FRTW in Types I, II and III construction, which call for the use of non-combustible materials or FRTW.

Section 2303.2 of the 2015 IBC defines FRTW as “any wood product … impregnated with chemicals by a pressure process or other means during manufacture” with a listed flame spread index of 25 or less and with “no evidence of significant progressive combustion” during testing for 20 additional minutes.

The product is subject to testing in accordance with ASTM E84 or UL723.

For wood products “produced by other means,” however, Section 2303.2.2 states “the treatment shall be an integral part of the manufacturing of the wood product. This treatment shall provide permanent protection to all surfaces of the wood product.”

This section of the code was unclear as to whether the wood must be impregnated with chemicals in order to qualify as FRTW. In such cases, one must go back to Chapter 2 Definitions, which defines FRTW as a wood product that is impregnated with chemicals by a pressure process or other means during manufacture, and which exhibits reduced surface-burning characteristics and resists propagation of fire.

Since Section 2303.2.2 did not reinforce the fact that FRTW must be a wood product that is impregnated with chemicals, some manufacturers took advantage and promoted their products as fire-retardant-treated wood, even though the treatment is only on the surface of the wood—in the form of paints and stains that are not integrated into the wood product and, therefore, do not qualify them as FRTW, according to code consultant Manny Muniz who assisted in the development of the code proposal (known as S262-16).

“This has frustrated the industry,” says Muniz, president of Manny Muniz Consulting in Lander, Wyoming. “Some [manufacturers] are using paints and coatings on their products because [Section 2303.2.2] did not say ‘impregnated.’”

He said in some cases, manufacturers touted their products as FRTW and did not reveal the “treatment” was not impregnated, but simply surface-applied paint or stain.

In the 2018 code, Section 2303.2.2 has been revised to clarify that the wood products must be impregnated with chemicals, even if that happens by means other than the pressure process. “The current wording could be misinterpreted to mean the wood products do not have to be impregnated with chemicals,” Muniz, a retired building official, says.

In addition, the 2018 code adds additional clarification at the end of Section 2303.2.2 that states: “The use of paints, coating, stains or other surface treatments are not an approved method of protection as required in this section.”

“It is important to get this across to jurisdictions so they do not allow the wood that did not have chemicals impregnated into it to be used, no matter which process was used during manufacturing,” Muniz says. The new language, he says, “will be a big help for jurisdictions.”

Widespread acceptance

Muniz estimates that many Type I, II and III buildings have been constructed with non-impregnated surface-coated wood that local code officials and contractors believed was FRTW.

Denver was one of the jurisdictions that accepted surface-coated wood for use in buildings requiring non-combustible materials or FRTW. Muniz says once his team explained the difference between chemical-impregnated wood and wood products with surface-applied treatments, the city stopped allowing the use of non-impregnated wood in buildings there.

In Minnesota, Muniz added, contractors had used the surface-coated wood in a five-story residential building “thinking that it was the right wood” because the product’s label looked like it was FRTW. “After failing to prove the suspect wood was equal in performance to FRTW,” Muniz says, the owner fired the contractor and replaced the non-complying wood with code-complying FRTW. “It was extremely costly to the owner and to the contactor, and they lost a lot of time to construction.”

The value of impregnated chemicals

Paints, stains and other surface-applied coatings do, in fact, provide some protection from the spread of flames. When applied as a finish to a building’s nonstructural interior wood surfaces—like walls, floors and hand rails, it offers a limited amount of fire protection, Muniz explains.

But for structural walls on the outside of buildings, those coatings fall short, both in terms of safety and code compliance.

FRTW is effective in retarding fire and is allowed by the code as a substitute for noncombustible building materials because the chemicals impregnated into the wood form a tenaciously adhering, hard char barrier when it comes into contact with flames.

Consider a wood log in a fireplace: It chars on the outside and burns somewhat slowly. But because the char scrapes off easily, it does not prevent the wood from continuing to burn.

Impregnate that same log with chemicals and the char becomes substantially harder and durable enough to protect the wood and retard the burning rate. And once the flame is quenched, the wood stops burning. That combined protection makes it suitable for use in construction.

For over a century, the most common way to impregnate those protective chemicals into wood has been through the pressure process. But over the years, alternatives to the pressure process have been devised for impregnating the chemicals into the wood. In response, the IBC has allowed pressure-alternative, chemical-impregnated wood to be substituted for the traditional products manufactured by the pressure process.

Language meant to allow for these new techniques became a shortcoming, however, when some manufacturers used the language to justify coatings as a means of producing FRTW, Muniz says.

The fix

The modified language in Section 2303.2.2 of the 2018 IBC, Muniz says, “makes it more clear to the jurisdictions that they shouldn’t be allowing products claiming to be FRTW that, No. 1, is not impregnated with chemicals, or No. 2, uses a paint or coating or stain as a method of protection.”

He adds: “These are just common-sense engineering principals.”

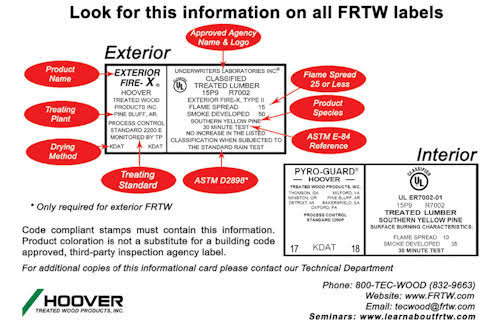

Muniz advises building officials to carefully inspect labels on FRTW. Fraudulent products, he says, often do not have labels at all or have labels that appear legitimate—until compared with the label requirements of the code.